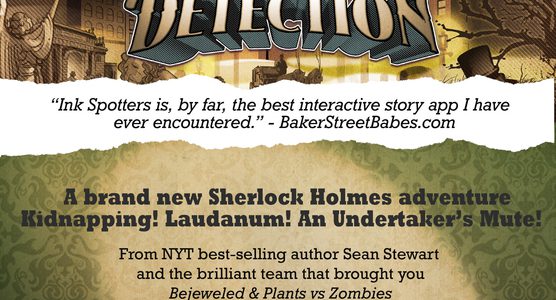

“Ink Spotters is, by far, the best interactive story app I have ever encountered.”

This line from the first review of our new app means a lot to me. Of course, as an entertainer, you always hope the audience will clap at the end of the show.

But in this case there is a more fundamental question going on about what constitutes “interactive story.” Usually when people use the phrase, they are talking about some variant of a Choose Your Own Adventure tale, where the reader gets to decide which course the story will follow. This gives a strong sense of agency, but – for me – also tends to undermine the real-ness of the fiction. A story is a series of real events that happen to imaginary people. When you offer me a selection of possible imaginary events that might or might not happen to imaginary people … things are getting pretty misty.

At that point, it really is your adventure you are choosing. The character has become a sort of Imperial Walker for you to ride around in while you make choices. This can be really fun – apparently the kids are into this whole “video game” thing – but it isn’t what I come to story for. Much of the pleasure of story, for me, is putting my self aside to experience what it’s like to be someone quite different – Sam Spade or Anne of Green Gables or Oliver Twist. When I choose my own adventure, I am doing the opposite – I make room for myself by erasing Anne or Oliver. In the massively successful video game franchise Halo, you never see the hero’s face. There is a reason for that. He doesn’t need one.

Because spending time with characters I enjoy is so much of what I like about story, Ink Spotters follow a different model; they tell a story of real events that really happened to imaginary people. In Ink Spotter #1, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson set out on an adventure when a young woman rushes into the flat at 221B Baker Street to announce, “The undertaker has stolen my lion!” The case takes them from Mayfair to Brompton cemetery, and they encounter parrots, laudanum, and an undertaker’s mute along the way. Your job is not to change those events, but to discover them.

Using your wits and following one clue at a time, you piece the story together until you have a complete understanding of events. Like Sherlock coming to a crime scene, you aren’t changing who the killer is – your job is to discover what really happened.

(In this sense, all stories are mysteries. Don’t you ask yourself on the first page who this character is and what her motivations are? You wonder about the relationships between characters as you are introduced to them – perhaps you are even puzzling out the rules of whole worlds like Middle Earth or Westeros. To be a reader is to be a detective.)

As a writer, I have spent the last fifteen years trying to find ways to let people engage with stories – to dive in and get their hands dirty and feel a great sense of agency … while at the same time respecting the integrity of stories themselves.

A character’s life can only matter if she has free will; in that way she is like the rest of us, despite being fictional. What we are trying to do with Ink Spotters is to give the characters that respect, while still giving the reader the fun, satisfying, hands-on experience the word “game” implies.

If you play Ink Spotter #1, you will not be able to change what Sherlock, Watson, or even the undertaker’s mute do by the tiniest bit. Which is exactly why I am so very, very happy that our first reviewer called it “the best interactive story game” she had ever seen.

To learn more, visit www.InkSpotters.com, or download Ink Spotter #1: The Art of Detection from the app store.